Foreword

Small businesses are agents of social change. They provide jobs, skills and training for those furthest from the labour market including young people and older workers, those with disabilities and mental health conditions, and those with low levels of educational attainment. Policy makers must recognise, reward and capitalise upon the invaluable role that smaller businesses play in supporting social mobility, wellbeing and fuller working lives. For this to be achieved policy makers must understand smaller businesses and how they promote good quality work. For example, smaller businesses often deliver flexible working through informal rather than formal processes. Small businesses can operate this way because of the personal relationships and bonds of trust fostered within their close ‘family’ environments.

The UK Government must expedite policy interventions to support smaller businesses to make real inroads into reducing the disability employment gap. Measures to support smaller firms to deliver work experience, apprenticeships and work placements (on which T-levels depend) are just as important to promote social mobility. Creating an inclusive workforce and UK economy that works for all – whatever an individual’s background and wherever they live – means reaching out to all groups that need help and support to thrive. Measures to help smaller businesses to employ ex-offenders, or to help service leavers consider the rewards of setting up their own business, have the potential to be game changers. And for certain ethnic minority groups which are disproportionately affected by unemployment, self-employment offers a chance to fulfil their potential, either in of itself or as a route into employment. We should not underestimate the power of inspiration and role models and we need a business support system that capitalises upon this.

Why does this matter? Because now more than ever we must find what binds us together, rather than what divides us. It’s the right thing to do, but it also makes economic sense. After all, boosting productivity is as much about diversity, flexible working, job design, employee engagement, and promoting wellbeing, as it is about infrastructure and digital technologies.

Community engagement

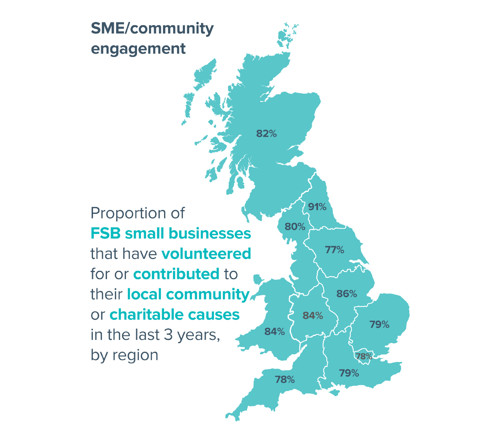

How small businesses have contributed to their local communities regionally.

Contribute

80% of FSB members have contributed to their local community or charity in the past three years

Flexible working

89 of Small Businesses offer some form of flexible working

Disadvantaged groups

95 % of small employers have taken workers from disadvantaged groups.

Older workers

...have at least one worker aged over 50

Work experience

41% of small businesses offer work experience.

Direct action

Small businesses donate time and skills to their communities

Executive summary

Smaller businesses are very often the heartbeat of their communities up and down the United Kingdom, but more needs to be done to understand the exact nature of their contribution, beyond the products and services they provide as part of their day job. The UK Government’s vision is one of better connected communities, more neighbourliness, and businesses of all sizes, which together strengthen society. This report demonstrates the extent to which small firms support and contribute to solving a number of challenges faced by our local communities. In it, we share insights gathered through in-depth survey work and qualitative evidence, collected from interviews with FSB members.

This report is split into five parts. The first section explores how smaller businesses contribute to their community and how they can be supported to do even more. The second part of this report focuses on smaller businesses as employers of labour market disadvantaged groups. Part three focuses on smaller businesses’ contribution to ‘Good Work’, for example in offering flexible working. Part four explores the issues many smaller businesses face in relation to the health of their employees. Finally in the spirit of supporting inclusivity, the final part of this report focuses on how service leavers can be encouraged to explore the opportunities and rewards provided through being self-employed.

Contribution to communities

FSB research found that small business community engagement is extensive across the country, with 80 per cent of FSB members stating they have volunteered and/or contributed to a local community organisation or charitable cause in the last three years. Our evidence suggests that small firms create strong civic engagement networks, which may help to foster greater trust within communities and, as a result, encourage more people to work together to help the community as a whole.1 Despite their day-to-day pressures, many smaller firms are committed to utilising their resources, skills and time in giving back to their local community.

In addition to the direct costs of new regulatory requirements for smaller businesses, policy makers must ensure they fully consider the indirect opportunity costs associated with any additional administrative burdens (for example as a result of tax and regulatory changes). Time spent trying to implement poorly designed or not well understood regulation takes away from the time that smaller businesses can spend contributing to their community.

Labour market disadvantaged groups

For communities to thrive, the 16.3 million people employed within small businesses must also thrive. The agility and adaptability of small firms means they are not only able to provide effective business ‘in-kind support’, such as donating resources to community organisations – especially in hard to reach areas – but they also act as a gateway into employment for those furthest away from the labour market. This includes people with disabilities, those with low levels of educational attainment and older workers. As the proportion of workers aged 50 and over continues to rise, so does the number of older workers employed in small businesses.

Unemployment is at record low levels, but we are far from real ‘full’ employment. The UK Government has the opportunity to fulfil the Conservative Party manifesto (2017)2 promise to incentivise small businesses to employ the most labour market disadvantaged people in our communities, by offering firms a one-year Employers National Insurance Contributions ‘holiday’ when they recruit from these groups.

Good work and work and health

Smaller businesses need greater support to enable them to contribute even more to the Good Work agenda and overcome challenges related to work and health. This is particularly important with regard to the employment of older workers and people with disabilities. Small businesses require a range of measures to assist them throughout the employment life cycle. The top three interventions small businesses would find helpful to employing staff are:

- Employer National Insurance Contributions holiday for one year for employing labour market disadvantaged groups

- Access to funds for workplace and non-workplace learning

- Ability to Reclaim Statutory Sick Pay (Percentage Threshold Scheme was abolished in 2014)

To realise the Good Work agenda for all workers, policy makers must focus on supporting smaller businesses to deliver on the ‘3Rs’, recruit, retrain and retain. This reports sets out various interventions which would help smaller businesses to achieve this.

1 Office for National Statistics, Social capital in the UK: May 2017.

Key findings

Community

- 80 per cent of FSB members have volunteered and/or contributed to a local community organisation or charitable cause in the last three years. Of those that have, the most common ways to contribute are by donating their time (38%) and providing skills, resources and mentoring (32%).

- 27 per cent of FSB small businesses hold a position within their local community.

- 42 per cent of small businesses engage with schools, colleges and youth organisations.

- 41 per cent of small business employers offer work experience either as part of the recruitment process or through their community outreach.

Employing labour market disadvantaged groups

- 95 per cent of FSB small business employers have employed at least one worker from a labour market disadvantaged group in the last three years, some of which include those:

- Aged 16-24 (58%)

- Aged 50 or above (78%)

- With a known disability or mental health condition (30%)

- With low levels of educational attainment (34%)

- With English as a second language (24%)

- Labour market returners (23%)

Good Work and flexible working

- 89 per cent of FSB small business employers offer all or some of their staff flexible working arrangements, including:

- Flexi-time or staggered working (63%)

- Reduced working hours (61%)

- Of those that have flexible working, 71 per cent recognise the benefits this has had, including:

- Reduction of staff absences (44%)

- Creation of new business processes (44%)

- Additional business cost savings (39%)

- Of those that offer flexible working, 36 per cent say that providing staff with greater autonomy led to the creation and/or development of a new product.

Work and health

Disability and mental health

- 11 per cent of FSB small business employers have at least one worker with a disability and 19 per cent employ at least one person with a mental health condition.

- Those that do are much more likely to provide flexible working to all staff (80% compared to 69% for all small employers).

Managing sickness absence

- 27 per cent of FSB small business employers have experienced short term health absences, 30 per cent have reported employee sickness lasting at least four consecutive days.

- 34 per cent say sickness absence has cost more than £1,000 in the last 12 months. For those that employ over 65s, this figure rises to 41 per cent.

Occupational health

- 10 per cent of FSB small business employers offer occupational health support.

- 41 per cent say they do not know enough about occupational health.

Recommendations

Further details on each of the above recommendations are provided in the full downloadable report below.

Click below to download the full report