Foreword

FSB welcomed the Spring Statement announcement that the co-investment requirement for nonlevy paying smaller businesses would be reduced from 10 per cent to five per cent from April 2019, and that the percentage of unspent levy funds that can be shared with non-levy paying smaller businesses (for example, in their supply chains) would increase from 10 per cent to 25 per cent. The provision of a further £5 million for the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education to introduce new standards and update existing ones is also a step in the right direction. However, far more needs to be done.

Smaller businesses need immediate support to meet the explicit requirement for a minimum of 20 per cent off-the-job training and to ensure they are not disadvantaged by the transition from frameworks to standards. Equally important is ensuring small businesses can access good quality training in their locality and benefit from incentives currently allowed for within the system. Establishing equilibrium in the relationships between businesses as consumers and suppliers is essential. Currently, smaller businesses simply cannot wield the same buying power as larger private sector employers to influence training provision.

While FSB does not want to see radical reform to the apprenticeship system, there are now serious questions to be answered in relation to the future sustainability of funding for apprenticeships. As levy funds are exhausted, policy makers must find solutions that are fair and equitable, and which do not lead to apprenticeships becoming unaffordable for smaller businesses. Both the Review of the Apprenticeship Levy and the Spending Review 2019 are important opportunities to make a true success of apprenticeship policy in England.

Apprentice reforms

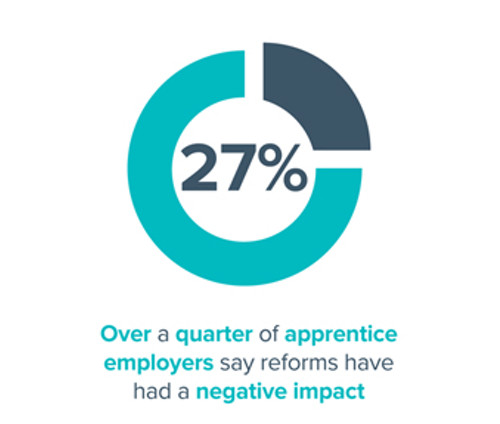

Over a quarter of apprentice employers say reforms have had a negative impact.

Top challenges - 1

Difficulty recruiting an apprentice

Top challenges- 2

Management time

Top challenges - 3

Off the job training

Age of apprentice

Majority of apprenticeships held by 16-24 year olds

Skill level

Majority of apprenticeships are intermediate to advanced

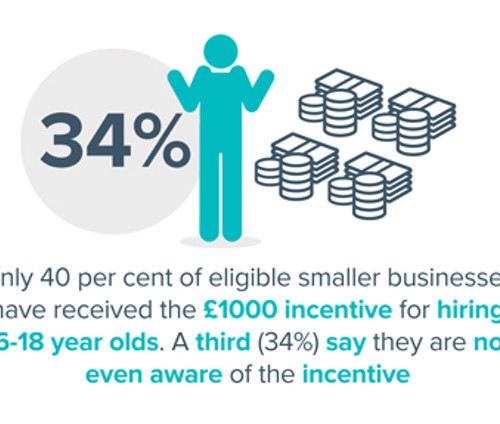

Government incentive

Many eligible smaller businesses have not received the £1000 incentive for hiring 16-18 year olds.

Increasing costs

Costs have increased.

Executive summary

This report shines a light on the impact of the apprenticeship reforms on small businesses in England. It should inform Government decision-making to improve the system, feeding into the ongoing Review of the Apprenticeship Levy and the upcoming Spending Review. This report is based on quantitative and qualitative data collated from FSB members. It is structured into four sections: post-reforms state of apprenticeships in small businesses in England; impact of May 2017 reforms on small businesses; training and assessment provision; and the future of apprenticeships.

The vast majority of smaller firms do not pay the Apprenticeship Levy, instead contributing towards training and assessment costs through co-investment. The apprenticeship system creates opportunities for smaller businesses to expand their workforce and upskill their existing employees. Apprenticeships help small firms to boost their productivity and address skills shortages and gaps. Therefore, a robust and fair apprenticeships system is critical if smaller businesses are to fully maximise the opportunities of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Equally important is the contribution of smaller businesses to social mobility. Small firms are found everywhere across England, including in rural areas, fringe towns and less favoured areas. They play a vital role in offering pathways for school-leavers into employment. FSB research shows that 92 per cent of all apprenticeships offered by smaller businesses in England are held by 16-24 year olds. Of those small firms that provide apprenticeships, 30 per cent have employed apprentices whose highest educational achievement is GCSE Maths / English grade C or lower (or equivalent), i.e. those with low educational attainment. Therefore, any Government policy which limits the ability of small businesses to offer apprenticeships will impact on smaller business ability to drive forward social mobility.

FSB research shows that the 2017 apprenticeship reforms have had unintended, negative consequences for smaller businesses. This report focuses on those reforms which have had most impact on smaller businesses:

b. Change in training and assessment provision geared at improving quality;

c. Introduction of co-investment of 10 per cent of training and assessment costs.

Of those smaller firms that employed apprentices both before and after the 2017 reforms, over a quarter (27%) say the 2017 reforms have had a negative impact on their business. FSB evidence suggests that the changes to the apprenticeship system – intended to significantly increase the number of apprenticeships by March 2020 and achieve the Government target of three million apprentices in England – have not, to date, worked for smaller businesses. Government statistics show that, compared to 2015/16, the proportion of Level 2 (intermediate) and Level 3 (advanced) apprenticeship starts fell sharply in 2017/2018, by 45 per cent and 13 per cent, respectively.[1] The vast majority (87%) of apprenticeships offered by smaller businesses are at Level 2 and Level 3. Smaller businesses are more likely to employ new apprentices (i.e. new to their workforce) than larger businesses.

Small firms have welcomed Government interventions on co-investment and transfer of unspent levy funding to non-levy paying firms. However, more must be done in the short-term to:

b. improve the quality and availability of training provision for smaller businesses,especially where the most common apprenticeships levels utilised are Levels 2 and 3, and;

c. ensure existing incentives, especially those that are currently passed down by training providers, are delivered to eligible smaller businesses.

In the medium to longer-term, FSB continues to have serious concerns about the likely exhaustion of the levy budget and the consequences for non-levy paying employers. Government expects the apprenticeship programme to overspend in the future given that the average cost of training an apprentice on a standard is around double what was expected.[2] The 2019 Spending Review and the Review of the Apprenticeship Levy present a vital opportunity to address these difficulties.

[1] Department for Education (2019) Apprenticeships and traineeships data. Accessed on 8 April 2019.

[2] National Audit Office (2019) The apprenticeships programme.

Key findings

Post- 2017 reforms state of apprenticeships in small businesses in England

- 87 per cent of all apprenticeships offered by FSB small firms are at Level 2 ‘Intermediate’ (49%) and Level 3 ‘Advanced’ (38%).

- 10 per cent of all apprenticeships offered by FSB small firms are at Level 4-7. Four per cent are at Level 6-7.

- 92 per cent of all apprenticeships offered by FSB small firms are held by 16-24 year olds, which is significantly higher than the national average of 56 per cent for all apprenticeship achievements in England (2017/18).

- 47 per cent of all apprenticeships offered by small businesses are held by 16-18-year olds. 44 per cent of all apprenticeships offered by small businesses are held by 19-24 year olds.

- Of those small businesses that have employed apprentices, many say they have hired from the following disadvantaged groups:

- Highest educational achievement GCSE Maths/English grade C or lower (30%)

- Long-term unemployed (9%)

- BAME background (9%)

- Mental health condition (7%)

- Returning to work after a career break (4%)

- Disability (4%)

- 48 per cent of smaller businesses that employ or employed apprentices, or wish to employ apprentices in the future, would be interested in offering part-time apprenticeships.

- 43 per cent of small businesses that employ or employed apprentices, or wish to employ apprentices in the future, are also interested in more flexible bespoke apprenticeships that can be adjusted to their needs, even if this requires more administrative time and effort on their part.

Impact of 2017 reforms on small businesses and apprenticeships

- Of those small firms that employed apprentices both before and after the 2017 reforms, over a quarter (27%) say the reforms have had a negative impact.

- The three biggest challenges for smaller firms when engaging with apprenticeships are:

- Recruiting an apprentice (42%)

- Management time (29%)

- 20 per cent off-the-job training (24%)

- Only 40 per cent of eligible smaller businesses have received the £1000 incentive for hiring 16-18 year olds. A third (34%) say they are not even aware of the incentive.

- 41 per cent of small businesses that employ apprentices report that their costs related to recruiting and training apprentices have increased.

- Small businesses based in rural areas (46%) were more likely to report increased costs associated with apprenticeships than those in urban areas (40%).

- Around one fifth (21%) of smaller firms that have employed apprentices after the 2017 reforms say they have had difficulty contributing 10 per cent towards training and assessment costs of apprentices.

- One fifth (20%) of smaller firms that have employed apprentices after the 2017 reforms have upskilled their existing employees or themselves using apprenticeships. The biggest barriers to this are the requirement for 20 per cent off-the-job training and finding funds for co-investment.

- Of those small firms that have employed apprentices or are seeking to employ, apprentices, almost half (48%) say they want control over the recruitment and administration process.

- Around a third (30%) of small businesses that have employed apprentices say they are dissatisfied with the ability of training providers to accommodate their needs. Over a third (35%) are dissatisfied with providers’ communications.

- Just over a quarter (27%) of small businesses that have employed apprentices rate the quality of training as poor. The same proportion do not think it was a good experience for the apprentice.

- 49 per cent of small businesses that have employed apprentices after the reforms say ‘quality of the training provider in my area’ is the main reason for the difficulties with finding a training provider.

Recommendations

Full details on each of the above recommendations areas are provided in the downloadable report below.

Download the full report